The War of 1812, lasting from June 18, 1812, to February 18, 1815, was a conflict between the United States and Great Britain. Its origins were rooted in British restrictions on U.S. trade and the kidnapping of U.S. sailors. Notably, this war coincided with the Napoleonic Wars, a series of European conflicts involving the French Empire and a coalition led by Great Britain.

The Napoleonic Wars

During the Napoleonic Wars, the British Royal Navy, led by Lord Nelson, achieved a significant victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This victory gave the British control over North American seas. Despite pressures from France and Britain, the United States maintained its neutrality. U.S. merchants, however, began exporting Spanish and French goods to European ports, impacting British West Indies products. In response, Great Britain initiated a blockade on French-controlled European ports, significantly affecting American trade and escalating tensions.

Impressment and Its Consequences

Amid these events, many British sailors deserted the Royal Navy due to the harsh conditions of seaside warfare. Some of these deserters joined the United States Merchant Marine, a group of U.S. civilian and federally-owned merchant vessels, to aid in retrieving their fellow deserters. The British Royal Navy began impressment, a practice where they forcibly conscripted foreign sailors, which further complicated the situation. Citizenship documentation was often lacking for American sailors, and British deserters attempted to forge paperwork.

Impressment served Great Britain in two ways: disrupting American overseas trade with France and bolstering their navy with additional sailors. This infuriated American political leaders due to the harm to U.S. trade and the violation of American sovereignty.

Rise of the War Hawks

In response to these challenges, American politicians known as War Hawks emerged. They advocated for war with Great Britain, supported U.S. expansionism, including annexing Canada and Florida, and sought to overcome Native American resistance in the west. The War Hawks’ rise to power in Congress was fueled by their opposition to British impressment and interference in free trade.

Political Developments

In 1811, two prominent War Hawks, Henry Clay and Peter B. Porter, assumed powerful positions in Congress. Henry Clay became Speaker of the House, and Peter B. Porter was named Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. These developments led to increased U.S. military spending in preparation for war.

Declaration of War

On June 4, 1812, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 79 to 49 in favor of declaring war against Great Britain, marking the closest congressional vote in U.S. history to formally declare war with another nation. On June 17, 1812, the U.S. Senate voted 19 to 13 in favor of the declaration of war.

Outbreak of War

On June 18, 1812, U.S. President James Madison signed the congressional declaration of war against Great Britain. Despite the overwhelming numerical superiority of the British Navy, most of the British Army was occupied in Europe, leading to a defensive British strategy. The Tecumseh Confederacy, a league of 15 Native American nations, also provided assistance to the British in their efforts to halt American expansion.

The Main Theatres of War

The War of 1812 unfolded in three primary theatres: the Northwest Frontier, the American South, and the Atlantic, now known as the main theatres of the War of 1812.

The Northwestern Theatre

The Northwestern Theatre witnessed some of the bloodiest and most brutal battles of the War of 1812. Both the British and American forces struggled to supply and reinforce troops in outposts located in the western Great Lakes region. Among the earliest battles here was the Siege of Detroit, occurring from August 15th to August 16th, 1812.

- The Siege of Detroit saw British forces, commanded by Major General Isaac Brock, and Native American warriors led by Shawnee leader Tecumseh, face off against U.S. forces commanded by Brigadier General William Hall.

- On August 15, 1812, British gunners began bombarding Fort Detroit with two ships, General Hunter and Queen Charlotte. On the morning of August 16, Tecumseh’s warriors crossed the Detroit River, followed by Brock’s brigade units.

- U.S. Brigadier General William Hull, fearing the size of the impending attack, surrendered the fort. Historians speculate he did so to protect his daughter, who was in the area.

- The loss of Fort Detroit prompted many more Native Americans to support the British cause on the northwestern front.

U.S. Military Leadership in the Northwest

- The loss of Fort Detroit led to Brigadier General William Hull’s removal from command. Brigadier General James Winchester took command but did not strategically seek to retake Detroit and was demoted to second in command.

- Major General William Henry Harrison then assumed command of the northwestern U.S. army and aimed to retake Detroit. He divided his forces into two columns, with Winchester leading one.

The Battle of Frenchtown

- General Winchester dispatched Colonel William Lewis and 700 U.S. soldiers to retake Frenchtown on January 21, 1813. They successfully recaptured the settlement.

- Although U.S. forces occupied Frenchtown, they expected British reinforcements.

- The Battle of Frenchtown began on January 22, 1813, when British Colonel Henry Proctor led an attack with 600 British soldiers and six cannons, accompanied by 800 Native American warriors.

- U.S. forces, while initially defending strongly, were eventually overwhelmed. When they retreated, they were ambushed, resulting in casualties.

General Winchester was captured by Chief Roundhead during the fighting, and U.S. forces surrendered Frenchtown to the British.

Marching Across the Detroit River

- British Colonel Henry Proctor marched uninjured prisoners across the frozen Detroit River to Fort Malden.

- Injured and unable to walk prisoners were left at Frenchtown and killed by Native American warriors.

- This event became known as the River Raisin Massacre, rallying more Kentuckians to enlist in the war effort.

The Atlantic Theatre

The Atlantic Theatre was another major area of conflict in the War of 1812. U.S. Navy vessels struggled to defend against British invasions along the Atlantic coast. The burning of Washington was a significant event in this theatre, as British forces invaded Washington, D.C., and set fire to government buildings.

The American South Theatre

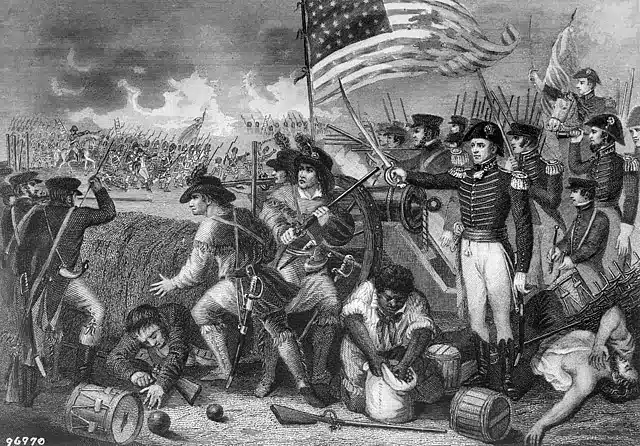

The American South Theatre witnessed significant fighting in the latter years of the war. The Battle of New Orleans, led by British Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and U.S. Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, was a major battle here.

- Ironically, the Battle of New Orleans took place after the War of 1812 officially ended, as news of the Treaty of Ghent signing didn’t reach the U.S. in time.

- In December 1814, over 50 British naval ships, commanded by British Major General Sir Edward Pakenham, sailed into the Gulf of Mexico to attack New Orleans.

- General Andrew Jackson declared martial law and quickly commissioned over 4,000 men to defend New Orleans.

- Preparations for the battle intensified following the sighting of British forces near Lake Borgne to the east of New Orleans. Over 4,000 men were commissioned to defend the city.

Battle of New Orleans: U.S. Forces

Diverse Defenders

Four thousand men from various backgrounds rallied to defend New Orleans. This diverse group included freed enslaved Africans, Kentucky militiamen, pirates, Tennessee militiamen, and Crayola farmers, all united in the defense of the city.

To bolster the city’s defenses, General Jackson ordered the construction of what is now known as Line Jackson. This defensive structure spanned from the Mississippi River to a large swamp. It comprised large logs and cotton bales coated with mud, providing protection for U.S. forces and their battery cannons.

As the battle commenced, the British launched two major offensive attacks. General Jackson responded by splitting his forces into two defensive squadrons.

One squadron, stationed on the east bank of the Mississippi River, consisted of 4,000 troops and eight battery cannons under the command of General Andrew Jackson.

The other squadron, positioned on the west bank of the Mississippi River, included 1,000 troops and 16 battery cannons led by General David Morgan.

The British Offensive

After several minor offensive strikes, the British army launched a full-blown offensive strike against U.S. forces on January 8, 1815. British Major General Sir Edward Pakenham led approximately 8,000 British troops in a head-on attack against U.S. defensive lines.

In the midst of the battle, the British army suffered significant casualties and lost General Pakenham to a fatal bullet wound. British General John Lambert assumed command, but by this point, the battle was already lost. General Lambert accepted defeat, and British forces retreated.

Remarkably, U.S. forces faced fewer than 100 casualties, while British forces suffered over 2,000 casualties.

Impact of the Battle of New Orleans

Although the Treaty of Ghent had officially ended the War of 1812, the decisive U.S. victory at the Battle of New Orleans had substantial domestic implications.

The battle played a pivotal role in kick-starting both the “Era of Good Feelings” and Andrew Jackson’s political career, ultimately leading to his presidency in 1829.

In April 1814, British public opinion soured due to heavy wartime taxation. Additionally, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was eager to conclude the War of 1812, as blocking American trade with France was no longer a priority.

Terms of the Treaty

The final agreement allowed both sides to retain their respective territories and exchange wartime prisoners. Diplomats from both nations also engaged in discussions about ending the international slave trade.

Overall Historical Significance

While the War of 1812 was a relatively small event in British history, it held great significance for the United States. It paved the way for a mostly peaceful century between the two nations until the outbreak of World War I.

The War of 1812 had profound consequences for Native Americans. They suffered the most casualties in proportion to their population during the war, and they had no European allies in North America.

Native Americans’ plans for a British protectorate Indian state in North America were thwarted. Most groups were left on small reservations with little to no power or influence over the new world.