On 6 February 2023, the Finnish newspaper Iltalehti, citing sources from Finnish foreign and security services, reported that Finland is prepared to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) without Sweden. It should be noted that Finland and Sweden had signed treaties for accession into NATO on 5 July 2022, largely in response to the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian War. However, among the 30 NATO member-states, Türkiye and Hungary have so far refused to ratify the treaties, thus blocking Finnish and Swedish accession into the multilateral military alliance. Since then, the Finnish government has consistently emphasized that Finland would not join NATO without Sweden. Nonetheless, following the recent downturn in Swedish-Turkish relations over the burning of a Quran in front of the Turkish Embassy in Sweden, the Turkish government has declared that Türkiye would continue to block Swedish entry into NATO but would not block Finnish entry into the alliance. Within days, it is being reported in the Finnish media that Finland is willing to join NATO regardless of Swedish accession. Thus, the Finnish quest for NATO membership has overturned the carefully crafted and meticulously balanced foreign policy that Helsinki has been pursuing since the conclusion of the Second World War.

Finland, a constituent part of Sweden between the late 13th century and 1809 and an autonomous grand principality under Russia between 1809 and 1917, obtained independence on 6 December 1917. Between 1917 and 1944, Finnish geopolitics was dominated by two concepts — the containment of the Soviet/Communist threat to Finland’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the creation of a Greater Finland, which would involve the Finnish annexation of Soviet territories.

Consequently, after the victory of the German-backed Finnish Whites in the Finnish Civil War against the Russian-backed Finnish Communists in May 1918, Finland adopted a ‘forward policy’ towards the war-ravaged Communist-controlled Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and engaged in numerous direct and indirect wars against the latter. Between 1918 and 1922, Finland assisted Estonia substantially in its war of independence against the RSFSR, launched several incursions into RSFSR-controlled East Karelia, facilitated pro-Finnish rebellions in Ingria and East Karelia, and engineered the Finnish annexation of Petsamo from the RSFSR.

During the Second World War, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) invaded Finland in November 1939 and occupied nearly 11% of Finnish territory by March 1940. In its turn, Finland participated in the German-led Axis Powers’ invasion of the USSR in 1941 in order to regain lost territories and to realize the aspirations of a Greater Finland. However, by 1944, Finland was knocked out of the war owing to the Vyborg-Petrozavodsk Operation of the Red Army, was forced to cede more territories to the USSR, was coerced into providing the USSR with numerous military-political concessions, and was compelled to expel Germany troops from Finnish territory through the Lapland War.

Following the Second World War, former Eastern and Central European Axis Powers, including Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and eastern Germany, were forcibly integrated into the Soviet sphere of influence. However, Finland preserved its national sovereignty and socio-political system through a peculiar form of diplomacy. Articulated by Finnish President Juho Paasiviki (1946-1956) and continued by his successor Urho Kekkonen (1956-1982), the Paasikivi-Kekkonen Doctrine advocated for close relations with the USSR during the Cold War in exchange for Soviet non-intervention in Finland.

As a result of this policy, Finland concluded the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance with the USSR in April 1948, rejected the US-initiated Marshall Plan, distanced itself from Western (as well as Soviet-led) military-political alliances, and demonstrated partially pro-Soviet leanings in its foreign policy. In turn, the USSR allowed Finland to retain its national sovereignty and its democratic and parliamentary political system, agreed to Finland’s desire to distance itself from strategic competition among the superpowers, and returned the Porkkala Peninsula (which Finland was forced to lease to the USSR for 50 years) to Finland in 1956.

Accordingly, the term Finlandization, literally meaning ‘the process of becoming like Finland’, referred to the foreign policy of a small state that seeks to preserve its sovereignty through maintaining good relations with its larger and/or more powerful neighbor. This strategy served Finland well during the Cold War, as Finland was able to stay out of the conflicts between the superpowers and maintain profitable economic relations with both sides of the Iron Curtain. However, it should be noted that the process of Finlandization was not universally popular in Finland, as Finnish nationalists viewed it as an externally-imposed system. Meanwhile, the US viewed the process negatively and feared that Western European states might be similarly ‘Finlandized’ by the USSR, resulting in the US loss of influence in Europe.

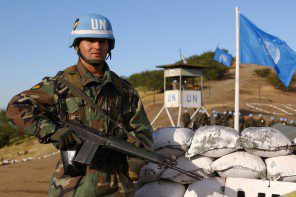

After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, a process of ‘de-Finlandization’, that is, the ending of Finlandization policies took off in Finland that slowly but surely reversed the Finlandization policies of the Cold War. Finland moved closer to the US-led Western World by abrogating the 1948 treaty, joining NATO’s ‘Partnership for Peace’ program in 1992, by joining the European Union (EU) in 1995, and by participating in NATO missions in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

However, on the other hand, Finland maintained good relations with Russia, refrained from directly joining NATO, and demonstrated a relatively balanced position on the renewed Russian–Western strategic competition until 2022, thus holding on to some elements of Finlandization. This has enabled Finland to obtain preferential trade relations with Russia and to ensure a steady inflow of cheap Russian energy. In addition, some political factions inside Finland are opposed to NATO membership and the Finnish people have long been divided about the issue. Nonetheless, Finland has quietly achieved interoperability with NATO forces over the years.

Ultimately, the eruption of the Russian-Ukrainian War in February 2022 caused the end of the Finlandization policies in Finland. Internal political consensus on NATO membership was largely achieved, and public opinion turned decisively pro-NATO for the first time in decades. Accordingly, Finland formally applied for joining NATO. Finnish accession to NATO would result in profound geostrategic implications, including the doubling of the size of the NATO-Russia border, the addition of strong armed forces at NATO’s disposal, the increase in NATO’s clout in the Baltic Sea, and the magnification of NATO’s power in the Arctic region, thus altering the regional balance of power.

Thus, the end of Finlandization by Finland has doomed the unique foreign policy strategy to certain marginalization in future discourses. Just before the outbreak of the war, French President Emmanuel Macron had reportedly suggested the ‘Finlandization’ of Ukraine as a possible solution to the Ukrainian crisis. However, now that Finland itself is ending Finlandization in earnest, the strategy is unlikely to provide any credible solution to the Russian-Ukrainian War and to future political crises across the world.

Md. Himel Rahman is a post-graduate student of Security Studies at the Department of International Relations in the University of Dhaka and a regular contributor to Roar Media. He is highly interested in international security, geopolitics, military–political history and Russian and Afro-Eurasian affairs.