Former US President Ronald R Reagan’s iconic “tear down this wall” call (Berlin, 1987) miraculously broke the Berlin Wall two years later as part of lifting the Iron Curtain. Of course, the United States was not the direct reason why: the Soviet Union was closer than the United States to financial bankruptcy from an arms-race dating back to World War II; and the quick passage from Leonid Brezhnev (1982), Yuri Andropov (1984), and Konstantin Chernenko (1985) to Mikhail Gorbachev (1985) produced a malleable leader whose perestroika and glasnost policy proposals were consistent with triggering an irreversible US rapprochement.

Like Reagan’s ‘wall’ moment against the Soviet Union, President Donald J Trump’s “TEAR DOWN THIS WALL” MOMENT addresses today’s chief US rival: China. Unlike Reagan’s explicit, fret-free, parsimonious call, Trump’s is a vacillating, opaque, and overloaded counterpart that may not produce the same dramatic outcome. For starters, whereas Reagan unwittingly addressed the leader of a sinking superpower, Trump confronts an ascendant superpower. In this eyeball-to-eyeball game, the Soviet Union blinked in the late 1980s, but the US is more likely to do so than China now.

Trump’s ‘wall’ moment took shape during his election campaign, when he demanded that China, the ‘currency manipulator’, should reduce its protectionist walls just as the US had done for China since, ironically, Reagan’s time. Of course, he had another more controversial ‘wall’ gripe, this time to build one, along the Mexican frontier. Though that deserves full consideration for its own right, this discussion concentrates on China and Far East Asia. Can the wall being broken down be used by Trump to break other ones?

Something happened on the way from the campaign trails to the Oval Office that diluted Trump’s Chinese demands. Whether it was the appointment of Indiana Governor Mike Pence as Vice President, or Trump’s daughter Ivanka as his unofficial representative, or even Rex Wayne Tillerson as Secretary of State or General James Norman Mattis as Secretary of Defense, the fact remains that a hitherto Trump villain, China’s Xi Jinping, landed in Mar-a-Lago even before Trump’s 100 days were over. Ostensibly playing golf with his host and receiving accolades that were simply unthinkable as late as October 2016, Jinping suddenly received praise for being less of a currency manipulator and more of a fairer trade partner, less of a reason to brandish protectionist measures against and more of a business partner, and less of an electioneering Trump’s villain and more of Chief Executive Trump’s strategic ally.

It was not that China had come clean on these various fronts, but Jinping did his homework well. On the one hand, he followed what Reagan’s sublime and effective performance against the Soviet Union did: seize an availing opportunity to put the ball in the adversary’s court. On the other, and evident in the 2017 January World Economic Forum gathering at Davos, Jinping capitalised on the haphazard, half-hearted US presence to re-enact what the US had been doing since the inaugural GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) ‘round’ in 1947: champion free trade globally. China’s trade policy reversal was not sudden, but long in the making. Through bilateral and plurilateral partnership agreements over the past two decades, China could boast in early 21st Century a wider and more functional global compass of partners than the US, and with fewer concerns than the US, whose trade is premised upon a series of equations like the General System of Preferences provisions, human-rights filters, trading-with-the-enemy sanctions, and so forth. More strategically, since paving the way through the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act the US became a global trade leader, China’s more carefully cultivated and unfettered credentials made it at least as solid a global captain. True, China’s trade agreements can be reduced to a one-sidedness that differs starkly with the ‘reciprocity’ in historical US deals, but in an age emphasising partnership numbers than sanction costs, China may still be reading the global trade roadmap more clearly than the US.

It was not that China had come clean on these various fronts, but Jinping did his homework well. On the one hand, he followed what Reagan’s sublime and effective performance against the Soviet Union did: seize an availing opportunity to put the ball in the adversary’s court.

Backtracking to the Soviet Union, Reagan’s ‘wall’ Berlin comment came amid his several summits with Gorbachev (in Geneva, 1985; Reykjavik, 1986; Washington, 1987; Moscow, 1988). Since they helped end the Cold War, Trump could begin with the Mar-a-Lago summit as his own ‘Geneva’, then prepare for his own ‘Reykjavik’, ‘Washington’, and ‘Moscow’ with adroit planning. It is becoming less of a tall order given other global crises, particularly the one being imposed by North Korea, with whose leader Trump has just opened the door for a summit “if the circumstances are right.”

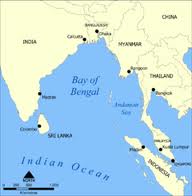

Trump could seize the opportunity of tearing down Chinese trade barriers (like Reagan, without being the direct reason why), by imposing other walls for China to dismantle. North Korea’s arrogant nuclear showmanship may just provide that opportunity. Before his 100-day marker as president had ended, Trump had moved a mighty fleet towards the Japan Sea for grabbing North Korean attention, but also to urge China to help lower North Korean walls. If he is able to do so without firing a shot, he may have accomplished what three of his immediate White House predecessors could not do: negotiations for a denuclearised peninsula, meaning the closest attempt to resolving the longest Cold War dispute and the only one that pitted US troops against the Chinese (in 1950).

It would be an astounding development, comparable to Reagan’s Soviet Union rapprochement behind his own bankrupting decision to develop the Strategic Development Initiative (Star Wars), blending well on at least three fronts. First, in South Korea’s presidential election in May 2017, Democratic Party’s Moon Jae-in emerged as the winner. He ran on a campaign that emphasised negotiations with his North Korean counterpart rather than confrontation, thus blunting any US intervention. Any US pre-emptive strike would thwart a Korean dialogue. Even in stationing missiles across South Korea during the last week of April, the US confronted a very vocal local opposition: Koreans do not want to go to war, and have hardly been drum-beating the way the US has. Going with the flow might start erasing the Trump administration’s negative impressions globally.

Second, the Damoclean Sword overhanging Japan would be lifted. As it is, since Japan has faced a lot of the test missiles from North Korea already, shifting from this concern would enable Shinzo Abe to turn more fully to pursuing his own economic reforms, given the sticky remnants of the 1990 recession. His parleys with Trump already hint at how Japan and the US could help each other out commercially and with investments, and thereby encourage the spillover effects on a still struggling global economy.

Third, Trump could cement an unthinkable China partnership that could also enormously uplift the global economy, not just by boosting trade, but also by shifting away from the spiralling arms-race. Since post-Cold War Republican administrations have been the strongest advocates and practitioners of an armaments policy, Trump’s tepid relations with that party would not necessarily obstruct any China agreement; in fact, he would be able to wrest his foreign policy coordinates from party control (through Vice President Pence), and infuse some robustness in his own leadership.

Of course, the ‘House of Sino-U.S. Rapprochement’ could also collapse dramatically even before a brick is laid. For a start, Trump does not have officials around him with adequate training, vision, interest, and professionalism to guarantee any rapport can be cultivated: snapshot decisions that have characterised Trump’s first 100 days (from White House Press Advisor Sean Spicer, former White House Chief Strategist Steven Bannon, Trump himself), cannot be assumed away, and may easily tax the patience that is so critically needed for the policy-approach to buttress long-term rapprochement.

Then there is China, which itself might stretch any contribution to defuse the Korean crisis to justify its South China Sea island construction, in turn antagonising Southeast Asian countries, if not the US. Though ASEAN leaders defused any immediate confrontation in their April summit, their concerns remain deep and tensions high. Above all, North Korea might itself rebel against being forced to denuclearise, especially when it does not have a history of congenial negotiating experiences to steady the ship in unchartered waters.

Russia would subvert any China-US rapprochement since it would deprive that country of the privileged extant partnership with China (evident in the Shanghai Cooperation Treaty).

A third concern is, in fact, North Korea, whose actions for a generation or more have defiantly ignored diplomatic procedures, so much so that they rekindle memories of another leader in Iraq a generation ago. After Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, when US Secretary of State James Baker induced Iraq to Geneva to negotiate a withdrawal in early January 1991, Iraqi Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz’s impressive participation could not prevent Saddam’s rejection. Operation Desert Storm followed, Iraq was defeated, and Saddam’s collapse may actually have started right then (in 1991, not with the 2003 invasion). Kim Jong-un should rehearse that predicament, since the armada awaiting him off-shore is capable of initiating such an operation. Of course, it would run afoul of China. One recalls how General Douglas MacArthur’s 1950 Yalu crossing prompted hordes of Chinese troops to push the US coalition all the way to the southern Korean tip before stabilising at the 38th Parallel three years later. That may not happen in a nuclear age, but provoking China is not the way to test that outcome.

Finally, Russia would subvert any China-US rapprochement since it would deprive that country of the privileged extant partnership with China (evident in the Shanghai Cooperation Treaty). One consequence: Putin could increase playing his spoilsport tactics elsewhere, for example, in Syria (as he already is), with Iran (a partnership recently struck could be put into high-gear), and, above all, Ukraine (completely unilaterally and at any time of Russia’s choosing).

Donald Trump is not the first Oval Office occupant to carry a shallow strategic mind. Harry S Truman’s bucolic approach concealed what turned out to be one of the most accomplished post-World War II US presidential tenures, erecting some of the critical institutions responsible for the relative global stability we have today: GATT, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the first and second strategies of containment against the Soviet Union, the European Recovery Plan (Marshall Plan), and so forth.

Relevant: TRUMP RETURNS TO SOCIAL MEDIA, WHAT’S NEXT?

Gerald Ford was another; but he was there for too short a time to have any strategic impact. Though Jimmy Carter came riding as a human-rights crusader, he left with deep realpolitik footprints, sowing the democratic seeds across East Europe, that culminated in Lech Walesa’s Solidarity uprising and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution in 1989, both transforming that region into what we see today; and likewise with the path-finding 1979 Camp David Accords that brought peace to Egypt and Israel. Finally, George W Bush would also fall into this category had not his father, George HW Bush, put in his own henchmen into his son’s administration (they were dubbed the ‘Vulcans’ by James Mann in a book suggesting how the Bush Doctrine of 2001 may have been written for the senior Bush ten years earlier, but put into cold storage because he lost the 1992 election: Richard Armitage, Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, among others, belonged to this group).

Flirting with a very august company, Trump’s shallow strategic mind may be less the problem than the missed opportunities. In the final analysis, he could leave the US with the most or fewest walls than since the Cold War. His own footprints will matter one way or another, and with it, the fate of the US as a world leader.