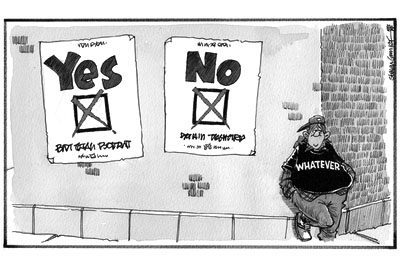

In an historic referendum on 18 September 2014, Scotland voted against independence from the United Kingdom. The overall result was quite close with 55% No to 45% Yes, with the split varying across areas. An unprecedented 84.5% of the electorate turned out to vote-the closest 83.9% turnout was seen in 1951. Among its various regions, Dundee was the most pro-Yes with 57.4% and the most emphatic No vote was in Orkney where 67.2% voted against independence. The independence referendum question was “Should Scotland be an independent country?”- which the voters answered with “Yes” or “No”.

The arrangement for this referendum was set out under Scottish Independence Referendum Bill, which was passed by the Scottish government in November 2013 and enacted as the Scottish Independence Referendum Act 2013, following an agreement between the Scottish and the United Kingdom governments. The path to referendum was paved by the Edinburgh Agreement signed on 15 October 2012. A total of almost 4.3 million people could vote, which included all European or Commonwealth citizens resident in Scotland and aged 16 or above, with few exceptions. The main campaign group for independence was ‘Yes Scotland’, while ‘Better Together’ was the main campaign in favor of maintaining the union. According to John Curtice, a professor of politics at the Strathclyde University, the result was not as close as the opinion polls had been predicting and that is not uncommon in such referendums where people are being asked to make a big change, as many people often draw back at the last moment.

Blame the Neoliberals

The question is why is it that so many believed that Scotland’s best place is out of the UK? For many who rallied for the referendum, it might have represented a way out of a situation in which they felt politically abandoned or deprived. It has to do with the major political and economic shift which took place in Britain 35 years ago. During the period from 1945 to 1979, British governments followed economic and social policies which put the needs of the majority people first. The post-war consensus meant that maintaining full employment was the governments’ first priority, supporting manufacturing industries, redistributing wealth and extending public ownership and providing the citizens with a comprehensive welfare state. When Margaret Thatcher was elected as the leader of the Conservative Party in 1975, things began to change. She was a neoliberal who didn’t favor socialist democratic policies. Her election as prime minister in 1979 signaled the end of the previous economic model with its substitution for a new one. While there was a big swing towards Thatcher’s Conservatives in London and other parts of Britain and voters were tempted by Thatcher’s programs, the Scots never were, and the number of Labour seats in Scotland and their share of Scottish votes actually increased.

Scotland has a long and proud history of socialism and its adherents preached a collectivist ideology, working class resistance and put people before profits. Throughout the period from 1979 to 1997, which can be termed as a period of Conservative hegemony, the party’s popularity gradually plummeted as their neoliberal policies led to the destruction of Scotland’s industrial base and mass unemployment. As a result the number of Conservative seats in Scotland fell from 21 to 10 in the 1987 general election and by 1097 the number reduced to 0. Scottish left-lenient voters hoped and wished that with a Labour government returning to power, they could break from neoliberalism and go back to more collectivist policies with support for industries and manufacturing ahead of the interests of bankers and speculators in London. However they were deeply disappointed by the New Labour government elected in 1997. The Blair government not only offered more neoliberal policies, but also followed even more aggressive and hawkish foreign policy and took Britain into a neocon war against Iraq in 2003-with fraudulent claims about Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction- alongside a hard-right Republican US president. Thus, Scotland’s disenchantment with pro-war, neoliberal Westminster elite grew, as well as their support for independence.

Eventually, the Scot’s vote for devolution increased from32.9% in 1979 to overwhelming 63.5 % in 1997. A decade later, opinion polls showed that the majority of Scots weren’t only satisfied with devolution, they wanted independence instead. This can be considered as a significant shift in a relatively short time span. It seems that neoliberalism doesn’t bring people together, but divides them instead, loosening the bonds of solidarity with changes in economic systems and encouraging individualism. Sir Ian Gilmour, a consistent critic of Thatcherism, put it most precisely in his book ‘Inside Right’: “If people are not to be seduced by other attractions they must at least feel loyalty to the State. This loyalty will not be deep unless they gain from the State protection and other benefits…Economic liberalism because of its starkness and its failure to create a sense of community is likely to repel people from the rest of liberalism.”

DevoMax

The referendum on Scotland’s independence posed the British state one of its most significant internal political challenges in its recent history- even more potentially significant than the immense mobilization of the anti-Iraq war movement. The British state has beenexisting for three centuries in its current form- through the industrial revolution, two world wars, and social upheaval on immense scale. The Scottish National Party (SNP)could have settled for an extension to the existing range of devolved powers, instead of a referendum with this all-or-nothing question had the British state’s managers not shown such intransigence which led to the dangerous existential crisis for the union itself.

In the months leading up to the Edinburgh agreement, there was lengthy debate about including a further option, what is commonly known as “DevoMax”. It was high on the political agenda and the inclusion of that choice was pressed by the SNP as a fall-back position and partly to keep up the pressure, while the UK government preferred the simple question of separation or not. In the meantime, much effort was given on defining “DevoMax”. Is has been commonly assumed that a third constitutional option (in addition to the status quo and full independence) would consist of Scotland gaining most powers including more taxation and spending, except for defense and foreign affairs. Finally it was stipulated in the Edinburgh Agreement that there would be a single straightforward choice of leaving or remaining in the UK- which was seen as a tactical triumph of the UK government.

Now that the Yes side has lost and the status quo remains, the Scottish leaders would press for more devolved powers. Various proposals have been offered on enhanced devolution from various blocks. Just 48 hours before the polling stations opened for the referendum, the leaders of the three main parties at Westminster- David Cameron, Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg signed a pledge to devolve more powers to Scotland, if Scots rejected independence. It had three parts, the first part of the agreement promised “extensive new powers” for the Scottish Parliament “delivered by the process and to the timetable agreed” by the three parties. The second says the leaders agree that “the UK exists to ensure opportunity and security for all by sharing our resources equitably”. The third “categorically states” that the final say on funding for the NHS will lie with the Scottish government “because of the continuation of the Barnett allocation for resources, and the powers of the Scottish Parliament to raise revenue”. The Barnett formula is the method used to determine the distribution of public spending around the UK. The pledge appeared on the front of the Daily Record newspaper seems to have been aimed prominently and squarely at the traditional Labour voters who make up a lot of the Record’s readership. The vow’s political purpose was transparent- to steady the Labour vote in the referendum- and has played its part. The question that remains is, will David Cameron will deliver on his Devo vow?

What explains the Fail?

The referendum on Scottish independence might have been a Machiavellian masterstroke by David Cameron- the failed referendum strengthening the Tories rule for ever more in the remaining UK, although he was certainly weakened by the nerve wrecking pressure. In addition, by allowing residents of Scotland to vote in a referendum, he demonstrated to the world that his government places the values of human rights and freedom above sovereignty gaining a position on the moral high ground for Britain, all without losing an inch of land. On the other hand, a different set of reactions swept over Scotland, with accusations of voting irregularities and vote-rigging conspiracy theories starting to swirl despite First Minister Alex Salmond, calling on pro-independence supporters to “accept the democratic decision. There could be many explanations as to why did the majority vote “No”, for example the referendum opened up soul-searching questions of what it meant to be British with the pro-union ‘Better Together’ campaign highlighting Scotland’s shared historical ties with its English, Welsh and Northern Irish neighbors and the allure of these shared historical bonds certainly have swayed some voters to reject independence. While the “Yes” camp’s case for independence might have attracted millions of voters, but for many, the task of building a workable, independent nation proved too daunting. Many felt that during times of financial instability, keeping the status quo was the safest bet and the “No” campaign’s slogan ‘Why take the risk?’ no doubt have played a part in fostering this view. According to the ‘Yes’ campaigners, ‘project fear’ was a concerted effort by the British establishment which certainly have worked. Most importantly, the UK government spread the message that Scots would be financially worse off after independence. As was the case in Québec, the bulk of the argument against independence rested on the potential economic and financial implications of secession which ultimately played an important role despite the “Yes” camp claimed that independence would create more jobs, protect the National Health Service, alleviate poverty and protect public services.

David Laitin, a Professor of Political Science at Stanford University, explained the failure of the Scottish Referendum through his theory of “private subversion of a public good.” According to him, the failure of the referendum was related to those who hypothetically publicly supported independence, but privately voted ‘no’. Voters in Quebec and Scotland were willing to vote ‘yes’ as long as they felt confident the referendum would fail.People would rather have the feeling of being a Scottish nationalist without having to pay the cost.Once polls pass the tipping point, the median voters would publicly claim “yes” and privately vote “no” which he termed as “private subversion”.Thus, a powerful constraint on winning independence referenda was within the people marching for independence itself who were the private subverters of public goods. He claims that although his theory is a conceptual formulation and not a general pattern, people can see it in different aspects in their lives such as voting for “linguistic normalization” in Spain and sending their children to England for their schooling or marching with “burn our draft card” rally in the Vietnam war years, and joining the National Guard. Thus, in his book titled‘Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the near Abroad’, he writes “when people personally subvert the goals of the very movement they have given their elected leaders a mandate to promote, that movement will fail” – which might have been the case in Scotland.

Peak of Nationalism?

Scotland has rejected independence and the result has been accepted by both sides, what awaits for Scotland is to see. But for one thing, it could have well been the high point for the cause of Scottish independence—not just in this campaign but for decades to come. It could be that the climate for Scottish secession might never again be as favourable as it has been this time and three conducive factors sustained the “Yes” campaign. First, there had been a Tory-led government in Westminster which allowed nationalists to argue that Scots were currently disenfranchised. Second, the Tory-led government is busy with state austerity on unprecedented scale, therefore giving the social-democratic critics with many ready instances of their failures. Third, there are still reasonable flow ofoil and gas from the North Sea which means that Scotland would be a rich country on its own. It could be highly unlikely that these three conditions will all be present again at any point in the next few decades and Scottish nationalists could thus find it harder and harder to argue that their country is being impoverished by Westminster or that it would be better off on its own. This could have been their best chance to make the case!The Economist had arguedthat even a small victory for the status quo would profoundly shake the union but it would not be enough to increase the chances of Scotland voting to push off in a future referendum-which is a sad fact for the Scottish nationalists.

The current status of Scotland lies somewhere between that of a traditional nation state and that of a mere region of a nation state.The UK is essentially England, a democracy with an 84% English electorate, or a multi-national state in which one component nation comprises 80% plus of the whole.England’s dominant role within UK has meant that it has never felt the urge to be free of the British state. The British nationalism that has emerged there, as a result, has been ethnic, seeking to unite the indigenous population against the perceived threat of outsiders. On the contrary, in Scotland, Wales and Ireland nationalism is the name given to the campaign for self-determination. The ethnic nationalism of the British National Party (BNP) excludes people on grounds of race, while the nationalism of the SNP, and of the supporters of the Yes campaign more generally, is a civic nationalism which promotes an inclusive society based on where you are, not where you’re from.For the civic nationalists, living in Scotland and accepting the laws of Scotland suffices for being Scottish; people’s ethnicity, religious affiliation, linguistic background and so on have no bearing on whether or not they are considered Scottish.With independence, many in Scotland hoped to take control of their own affairsand to be able to build a society founded on ideals of empathetic concern for the disadvantaged, democracy and a strong civil society. They hold a dystopian view of UK- a violent and unequal society, its economy skewed towards finance capital, one where the super-rich live in gated communities guarded by private security, while large ghettoes are filled with a desperate underclass and the middle class works long hours to pay for private education and private health insurance to keep themselves and their children out of the ghettoes. They hoped that an independent Scotland had the chances of resisting such fate, and moreover, could provide a model for their neighbors by showing there is an alternative.

This referendum may have ended one debate in Scotland for now and Scotland wakes up still part of the United Kingdom. The leader of the SNP and the then Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond gracefully accepted the democratic verdict of the people. It might be mentioned that Mr Salmond resigned the leadership of the SNP hours after Scotland had delivered its 55-45 per cent verdict in favour of staying in the union. One might argue that with the turn of a new generation and most of the veteran unionists gone in the coming decades, independence for Scotland would be inevitable. However, what’s known as the West Lothian question hasn’t been answered yetsince it was first asked in 1977 (the question was, Why should the MP for Blackburn in West Lothian in Scotland be able to vote on English matters when the MP for Blackburn in Lancashire can’t vote on Scottish issues?). And the explosive question of where power lies in the UK is yet to be resolved.

The writer is Deputy Manager (Program) Bangladesh Institute of ICT in Development.