Small states are increasingly recognized as important actors in international politics. On the one hand, they exist in a large number; on the other hand, they have the potential to determine changes in international politics. However, how to define smallness? We are yet to get a unanimous definition of a small state. Athough all sovereign states are nation-states, they vary in terms of their power scale and status quo in international relations. Unless there is a standard and unique definition for what constitutes a small state, it is overwhelmingly challenging to structure a foreign policy framework for small states.

Quest for defining a small state

In the twentieth century, the number of states kept rising because of the break-up of the Hapsburg Empire in 1919, then of the British, French, and other European empires through decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s, and of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. In the aftermath of WW-II, the fundamental question of the survival of small states amongst the bigger powers was raised due to the two superpowers’ power race and maneuvering to get more access in establishing their own hegemony.

Different studies of “small states” have distinct characterizations. Even there is substantial disagreement over what indicators should be used to define a small state. Defining terms such as ‘weakness’, ‘power’, and ‘size’– especially, definitions that apply over time and space – has been proven difficult in international relations.

Morgenthau said, “A Great Power is a state which is able to have its will against a small state which in turn is not able to have its will against a Great Power.” Yet “a Great Power could easily sink to the level of a second-rate or small Power, and a small Power could easily rise to the eminence of a Great Power.” Did Morgenthau mean a small power as a small state?

Another definition comes through this line of ‘power’, and is recognized in negation. According to Neumann (1992), Small states were all those states that were not great powers and that were not consistently insisting on being referred to as middle powers like Australia, Canada, South Africa, etc.

Fukuyama believes that beyond territorial size, a ‘small’ or ‘smaller’ state often refers to a state with little or less government involvement in society or the national economy, and so on. According to Keohane, a ‘small state’ is one whose leaders consider that it can never, either acting alone or in a small group, make a significant impact on the globe.

Galtung has found the ranking order of states based on aggregate variables explaining more the nature and ratio of interactions between states than other criteria like the structure of government or executive, societal and political organizations or instrumental attitudes etc. In general definition, a state will be considered as a small state when it is nominal in size (i.e. territory, population, wealth and economy, military capability) and coming up (developing as a state) in a compressed form.

Barston suggested four approaches to define the term “small state”:

(1) Setting an upper limit on, for example, the population size,

(2) Measuring objective elements,

(3) Analyzing relative influence, and

(4) Identifying characteristics and formulating hypotheses on what differentiates small states from others.

Essentially, the small state is beset with a terminological and theoretical quest that holds that the overwhelming dilemma faced by small states is its inability to protect themselves, either militarily or economically, against encroachment by larger and stronger powers.

Size variable

Size is merely a variable and, furthermore, is relative; Poland is a large state when compared to Lithuania but a small state when compared to Russia. Relative notions of power can also be linked to a state’s self-image: Canada is a ‘medium’ power economically and is the world’s second-largest country in terms of land mass, but despite these apparent advantages, feels dwarfed (and often slashed) by its larger neighbor to the south. Relative definitions can also take into account the factor of influence. Nigeria, a large state in terms of both area and population, nevertheless is considered a small or weak state in the international arena because of the lack of influence it can exert on international affairs. The key assumption, according to Vital, was always that it is a combination of size, material resources, economic development, geographical location, and military might which determines the extent to which a smaller state enjoys the capacity to ‘perform as a resistant rather than vulnerable and active rather than a passive member of the international community’. David Vital tried to offer a comprehensive definition in his famous book titled “The Inequality of States — a Study of the Small Power in International Relations”. He settled the definition via some upper limits:

“(a) a population of 10-15 million in the case of economically advanced countries; and

(b) a population of 20-30 million in the case of underdeveloped countries.”.

The size of the population is not a strong separator because in the third world, there are many countries that are overwhelmingly populated. Among those states, most of them have limited natural resources but massive human resources. Bangladesh is an ideal example of that category. It has a territory of only 56,000 square miles, but more than 160 million people are living here with limited natural resources, insufficient military power, and an economy still in its developing phase. These indicators show Bangladesh as a qualified small state. Perceptions of a state’s size may be linked to its geographical position relative to its neighbors but is not contingent on physical contiguity. Maurice East suggested defining small states by their population, land area, the size of their economy, and military. Whereas for Olafsson the key dimensions of small state size are the state’s population, its geographic size, and its Gross National Product (GNP).

Security dynamic

Robert Rothstein rejected the notion of a definition of a small state based only on objective or tangible criteria. According to him, “A small power is a state which recognizes that it cannot obtain security primarily by the use of its own capabilities. And it must rely fundamentally on the aid of the other states, institutions, processes or developments to do so; the small power’s belief in its inability to rely on its own means also should be recognized by other states involved in international politics.” He claimed small states enter alliances to enhance their security due to their peculiar security situation. In the security dimension, small states are most often seen in a passive, reactive, or even negative light, contributing little to global security and in some cases even acting to destabilize it.

Keohane criticizes the definition of Rothstein. He argued, “A great power is a state whose leaders consider that it can alone exercise a large, perhaps decisive, impact on the international system; a secondary power is a state whose leaders consider that it can exercise some impact, although never in itself decisive, on that system; a middle power is a state whose leaders consider that it cannot act alone effectively but may be able to have a systematic impact in a small group or through an international institution; a small power is a state whose leaders consider that it can never, acting alone or in a small group, make a significant impact on the system.”

It is very difficult to set security as a base standard to differentiate small states from big ones. However, the issue of security cannot be ignored. Security most of the time ended in military power capacity. Military capabilities are a key factor in status quo determinants in international politics. But military capabilities cannot be the major scale of separator because it relies on technological and scientific advancement as well as economic support. Unless the state is forward in these sectors, her military strength is only for the time being.

Is ‘Weak State Theory’ applicable to the definition of a small state?

How does one define a ‘small’ or ‘weak’ state? Once a state is reckoned to be past a certain threshold, it is no longer considered to be ‘small’ or ‘weak’. Weak State Theory focuses on the issue of security and argues that a state’s independence (and ultimately its statehood) must be questioned if the state is militarily dominated by another state, as argued by Olafsson. Another scholar Professor Michael I. Handel figured a definition of a small state in his book “The Small States in International Politics and Organization” (1981), “A small state … is a state which is unable to contend in war with the great powers on anything like the equal terms” (p. 36). He argues that “the position and relative security of any weak state be gauged in terms of the specific international system in which it is operating … Even at the same period of history, weak states located in different areas have different neighbors and thus face different problems … Therefore, when speaking of the ability or inability of a weak state to defend itself, one must immediately ask, ‘Against whom?” However, according to Handel, small states are “by no means an impotent, helpless victim of the system, By contrast, some of them are quick to take advantage of the opportunities arising from the nature of any given international system”.

Economic condition

According to both liberal and Marxist perspectives, a state’s fundamental objective is to pursue economic interests. Economic theory suggests that small states may have intrinsic disadvantages (Easterly and Kraay 2000, Alesina and Spolaore 2003, World Bank 2008). In the economic dimension, the concentration is on the ability of small-state economies to survive in a world where economies of scale still dominate. For Karl Deutsch, a small state could be understood as a state whose GNP was less than 1 percent of the total world GNP. From earlier days debates on the “definition of small state” economic power emerged as a key determinant. Singer claimed that the GNP of a state indicates its potential war-making capacity which means the chances of becoming a warlord. But setting it as a benchmark for differentiating small states from great and middle powers is not an easy task. Academics fall into theoretical war because of Gross Domestic Production (GDP) – Gross National Production (GNP) contrasting relations. GDP does not show a real figure of national income and GNP does not show a real productivity figure. Despite a strong economy Singapore is struggling to avoid penetration from Malaysia, the United States, and China. It is relying on the United States for its national defense. On the other hand, Singapore is not privileged with huge natural resources but it has very skilled human resources. Small size may limit an economy’s scope for diversification. Many small states are islands or landlocked, and face problems of remoteness. Small states produce only a few items and import more than the rest, and hence are more exposed to trade shocks. They are disproportionately exposed to natural hazards like hurricanes, and floods as well.

Definition from the International forum

A study produced by the United Nations Institute for Training and Research in 1971 quoted the UN Secretary-General’s definition from 1966 which defined small states as “entities which are exceptionally small in area, population, and human and economic resources.” (UNITAR 1971:29) The report concluded that smallness “is a comparative and not an absolute idea.” In the United Nations, the then Singaporean Permanent Representative Ambassador Chew Tai Soo helped to create in 1992 an informal grouping called, the Forum of Small States (FOSS), to serve as a ‘platform for small states’ – in this case, those with a population of 10 million or below — ‘to exchange ideas on issues of shared concerns’. The grouping comprises 105 of the 193 members of the United Nations as of now.

The Commonwealth Secretariat’s definition of ‘small states’ is quite straightforward. It is countries with a population of 1.5 million or less, also possessing unique special developmental challenges such as limited diversification, limited capacity, poverty, susceptibility to natural disasters and environmental change, remoteness and isolation, openness and income volatility (interestingly, it also included larger member countries such as Botswana, Jamaica, Lesotho, Namibia, and Papua New Guinea because they shared many of the characteristics of small states). The World Bank identifies small states as countries with a population of under 10 million and which rank above the 75th percentile globally for ‘Political Stability and the Absence of Violence’ under its World Governance Indicators.

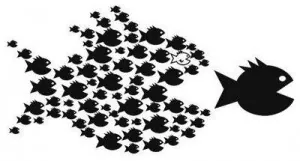

The power status quo may be the answer

As opposed to size, most international relations scholars generally categorize states according to the dimension of power. The overwhelming dilemma faced by small states is their inability to protect themselves either militarily or economically against encroachment by larger and stronger powers. Powerful states (especially the most powerful states known as ‘great powers’ or ‘superpowers’) matter most in international relations. These great powers and superpowers – with few exceptions – have created a de facto situation among states where power begets power, or what one scholar has termed the ‘golden rule’ of international relations: “He who has the gold makes the rules.”

If this entire series of key factors could be compiled and compressed into creating an indicator to frame generalized and common definitions, that might see the end of a history of arguments on defining small states. But the state itself is a salad of political matters. It is of paramount importance to categorize the political environment and settings in order to define a small state. The following factors need to be taken into account:

a. A small state is usually guarded by a guardian neighbor, and in most cases, it is her ancestor from whom she succeeded in self-determination and independence. There is hardly an exception to that.

b. According to the category of the size it could be populated land with a nominal territory and limited natural resources.

c. It may hardly acquire enough military capabilities for national security.

d. It is very much challenging to set a standard or qualified geo-political & geo-strategic importance. Because these elements work like determinants and act like dynamic dimensions.

In politics, nothing can be estimated or evaluated directly. All the political debates need to be justified through prisms. If all the factors of debate is complied and generalized into a definite frame that can describe all the small state through the same unique prism then, possibly, the definition will be figured like this:

A small state is a nation-state that has a nominal territory with a population of any size, hardly effective or no military power, limited natural resources, and an emerging or struggling economy.

In the current multipolar world of the 21st century, the international political landscape has undergone rapid changes. The practice of annexing small states for regional or international power succession is no longer feasible. Small states have emerged as a significant force. Although debates on their definition may continue, their impact and effectiveness as dynamic instruments, either unilaterally or multilaterally, will not diminish. It is now time to reverse Thucydides’s assertion that “right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in powers, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must,” and acknowledge the importance of small states.

The writer is a member of the Editorial panel of FAIR