On January 11, 2023, Russian fighters occupied Soledar, a mining city in the Donbass region and home to one of Europe’s largest salt mines, after nearly six months of vicious fighting. The Russian occupation of Soledar terminated one of the heaviest and bloodiest urban combats in the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian War. What is surprising here is the fact that the Russian fighters who participated in the intense conventional combat for Soledar are not part of the regular Russian Armed Forces; rather, they belong to a Russian private military company (PMC), the Wagner Group.

The Wagner Group, created in 2014 by Russian entrepreneur Yevgeny Prigozhin (reportedly close to Russian President Vladimir Putin) and now headquartered in Saint Petersburg, was initially a comparatively small organization and largely consisted of Russian ex-military servicemen. It came into prominence by taking part in the swift Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 on the Russian side and the Donbass War in 2014-2015 on the side of the self-declared Donbass republics (now integrated into Russia). While private military companies are illegal under Russian law and the Russian government has denied having any sort of contact with the Wagner Group until 2022, the Wagner contractors receive military training in the facilities of the Russian Ministry of Defence (MoD).

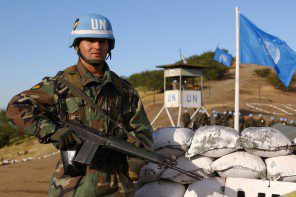

Over the years, Prigozhin’s Wagner Group has greatly expanded in terms of personnel, equipment, operational capacity and geographical scope. Since 2015, Wagner contractors have served as the ‘shock troops’ of the Syrian Arab Army, in addition to acting as frontline advisors, fire and movement coordinators, forward air controllers and security guards for hydrocarbon sites. Since 2018, they have served as the ‘spearhead’ of the Central African Armed Forces, acting as frontline commanders, military instructors and security guards for diamond mines, and directly controlling most of the frontline units of the Central African Armed Forces. Since the same year, they have worked as the ‘cream’ of the Libyan National Army (LNA) based in eastern Libya, serving as frontline advisors, snipers, artillery spotters, air defense troops, and security guards for oil fields. Since 2021, they have served as the ‘stormtroopers’ of the Malian Armed Forces, acting as military instructors, frontline advisers, and commanders of offensive operations. Moreover, Wagner contractors have been active in various capacities in a number of other states, including Sudan, Madagascar, Venezuela, Mozambique, and Burkina Faso.

The intervention of the Wagner Group has been instrumental in propping up the Syrian, Central African, and Malian governments, and the LNA. They have acted in close concert with the Russian government in each of these cases, acting as force-multipliers for the official Russian involvement and paving the way for expanded Russian influence in the Levant, North, West, and Central Africa, and as far as South America. They have been a useful tool for the Kremlin, helping reduce official Russian military losses in foreign battlefields, assisting in waging ‘proxy warfare’ against Russia’s rivals, and providing them with the benefit of ‘plausible deniability.’ They have directly clashed with US troops in Syria, shot down US and Turkish drones in Libya, pushed out the French from the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali, and targeted US mercenaries in Ukraine.

However, since the inception of the Russian-Ukrainian War in February 2022, the ‘plausible deniability’ came to an end, with the Wagner Group taking an increasingly active and vocal part in the war alongside the regular Russian Armed Forces, especially in the Donbass region. Wagner contractors have played important roles in Russian victories in the Battles of Popasnaya, Severodonetsk, and Lysychansk, and have been crucial in the Russian victory in the Battle of Soledar. In the ongoing months-long Battle of Bakhmut, which has been described in the media as a ‘meatgrinder’ for Ukrainian troops and a Stalingrad-esque carnage, Wagner contractors have reportedly ‘decimated’ several top-notch Ukrainian brigades in conventional warfare. In a war in which the regular Russian Armed Forces have suffered several setbacks, the name of the Wagner Group has mostly been associated with military success. In addition to fighting effectively in conventional and urban combat, the private military company has waged a robust public relations (PR) campaign and information warfare against Ukraine and the West.

As of now, the Wagner Group is probably the largest and strongest PMC in the world, possessing its own armored forces, artillery, air defense batteries, electronic warfare units, special forces, intelligence teams, and even an air force. Its recruitment base is now much more expansive. Even before the Russian-Ukrainian War, Wagner contractors included not only Russian but also Ukrainian, Belarusian, Moldovan, Armenian, Serbian, and Syrian citizens. After the outbreak of the war, they have reportedly started recruiting citizens of Central Asian and African states. Moreover, thousands of inmates from Russian prisons have been recruited by the PMC with promises of freedom, who are now participating in the war against Ukraine. Thus, the Wagner Group, initially thought to be a Russian version of the US PMC Blackwater (now rebranded as Constellis), has far surpassed its US counterpart in terms of material power and political influence.

However, the meteoric rise of the Wagner Group has generated a number of concerns among a number of actors. For instance, the PMC is notorious for its unorthodox and ruthless methods of operation. It has used prohibited weapons (for example, land mines in Libya), allegedly participated in massacres (in Central African Republic and Mali) and killed deserters (in Syria and Ukraine). Such incidents have caused concerns among human rights monitors, and have been utilized by Western states to push their own anti-Russian information warfare. Moreover, companies linked to the Wagner Group have obtained mining concessions in a number of states in which they operate, raising the specter of neo-colonialism and economic exploitation.

Moreover, the extensive involvement of the Wagner Group in the Russian-Ukrainian War has increased the political profile of the organization and its controller, Prigozhin, inside Russia. Prigozhin has personally recruited prison inmates for the private military company and promised them freedom, thus directly flouting Russian law and potentially undermining the ‘legal state’ meticulously built by Russian President Putin since the early 2000s. In addition, Prigozhin has openly criticized the Russian MoD for its supposedly ‘inefficient’ handling of the war against Ukraine. The Russian MoD has so far generally refrained from directly mentioning the name of the Wagner Group in its daily briefings about the Ukrainian War, and accordingly, in its coverage of the Battle of Soledar, they omitted the role of the Wagner contractors. This has led to a further row between the Russian MoD and the Wagner Group.

In medieval Europe, states lacked the monopoly over the instruments of violence, and accordingly, mercenaries played an important role in politics and warfare, even to the extent of threatening states. The current era, which is sometimes defined as an era of ‘neo-medievalism,’ has been characterized by the privatization of the means of violence, leading to the rise of organizations such as the Wagner Group. While the Wagner Group is currently under the control of the Russian government and is diligently serving the interests of the Kremlin, it is in possession of substantial means of violence, and taking into account its ‘beyond the law’ operation, its rising political profile, and its growing material power, there are possibilities that it might emerge as a ‘state within the state’ in Russia in the unforeseen future.

Md. Himel Rahman is a post-graduate student of Security Studies at the Department of International Relations in the University of Dhaka and a regular contributor to Roar Media. He is highly interested in international security, geopolitics, military-political history, and Russian and Eurasian affairs.