Frankly speaking, I have no idea of the number of madrasa-going students in Bangladesh. We do not expect even a rough statistic on the number of Senior, Junior, Wahhabi and Shrine-based madrasas in Bangladesh from the related department of the government as well. Of course, it is true that the operational state of most of the departments and ministries is the same. Nobody seems to keep the necessary reliable data; everybody acts only upon the orders of the superiors. Nevertheless, although lacking enthusiasm, the ministries nowadays are trying to keep some numerical data, only because our foreign donors and lenders, nowadays, do not want to commit to any undertaking without looking at some quantitative information and appraisal. But I can say without a shadow of a doubt that, if asked, the concerned ministry would not be able to produce even a fictitious count of the number of madrasas and their students. They can only give some information about those madrasas which receive some form of monthly assistance or a yearly lump sum grant from the government. The madrasas that are beyond the sphere of government assistance and will remain so; the madrasas that deem taking government assistance to be grave sin; the madrasas that are located at the houses of Pirs and their Dargahs; the madrasas that run on the donations of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha; the madrasas that are run by Wahhabis in a strict Christian Missionary-style — the number of all these madrasas together and the extent of their student population are unknown, and—though not impossible—a very hard thing to know indeed. After visiting many towns and villages of Bangladesh, I have come to the conclusion that the number of madrasa-students is very close to the number of students studying in the mainstream educational institutions. And contrary to popular yet vague believes, the education system of all the madrasas is not uniform as well. The madrasas which got government approval and are under the Madrasa Board have one type of curriculum, where a bit of English, Bengali and other modern subjects are taught. The teaching method is no way less amazing: there is only one teacher for mathematics, English, Bengali, social science—all these subjects. But the number of such approved madrasas is totally insignificant compared to the vast assortment of madrasas. Nonetheless, some students from these government-approved-madrasas, after completing degrees like Jamaat-e-Ula or Title, do go on to enroll in colleges after appearing for SSC. The rest of the vast number of Madrasas across the country follows a variety of curricula. Some follow Deoband, others follow word for word the curriculum of the Calcutta Madrasa established by Warren Hastings. Still others follow the curriculum developed during the era of Aurangzeb. On the other hand, in Junior Madrasas elementary lessons of Arabic, Urdu and Persian languages are generally given. The students there are made to read Raah-e-Nijat in Urdu for religious education; they also study Mawlana Saadi’s famous Persian books like Karima, Gulistan, Bostan, Pandenamah etc. One common point of view amongst the madrasas is: the older the curriculum of a madrasa, the more is its pride. Those students who go to colleges and universities after finishing madrasa education take up jobs in various sectors just like their college and university-going classmates. But the main challenge they face in obtaining government service is that, most of the times, their age exceeds the maximum age limit for entering such jobs, as they come to general education after completing madrasa at a relatively advanced age. A portion of those who pass Jamaat-e-Ula, Title, Fazil etc. become teachers themselves in madrasas, or—if they have certificate of HSC—join schools in the general stream as teachers of Religious Studies. The other portion makes a living by becoming Imams and Muezzins at mosques; by teaching the Holy Quran and Amparah at Maqtabs; by helping to slaughter chickens, goats and cows in accordance with Islamic rules; and by performing Quran Khawani. They are even compelled to resort to going from house to house reciting Fatihah and conducting Zeyarats on demand; giving Islamic sermons and speeches to the public; performing roles of traditional healers through offering Duas, giving out blessings, tabij and holy water, and casting out evil spirits etc. for making a hand to mouth living. A student of the general line, after graduating from university, can switch jobs if s/he is not happy with the salary; or, if member of any tread union, can bargain for pay rise and other facilities through various means. The Madrasa students with Jamaat-e-Ula or Title degrees have to spend more time in educational institutions than those of university degree holders; but what do they get out of this? Do they enjoy the same privileges as the university, medical college and engineering college students? Can an Imam or a Muezzin or a Munshi press, in any way, for a fair salary? Surely, the growth in number of Munshis and Mawlanas in the country is outnumbering the growth of that of mosques and madrasas. The environment of the madrasas is such that the students do not acquire any professional expertise; the structure is so medieval that the students cannot even think of getting trained in any trade or taking up any other profession after graduating from them. Nowhere in the Muslim world occurs such colossal waste of valuable human resources in the name of religious education. Neither have the madrasa-teachers and students engaged in any meaningful discussion regarding their problems and demands, nor have the cognizant sections of the society paid any attention to them. The so called educated people of this country look down on the madrasa-educated in a fashion which is totally irrational and inhumane. This attitude is dangerous and will give birth to grave consequences for the country. Apart from using them for petty political gains by some vested quarters, no one has ever thought of solving the problems these people face or about their total wellbeing. The political parties and student organizations of this land have never paid attention to the madrasa students. As a result, clouds of medieval darkness still hover over the madrasas. Any of the modes, values and enquiries of the modern era seldom gets a chance to sparkle amidst such an environment. Inquisitiveness, which lies at the heart of the philosophy of science, never dwells in the madrasas. So, there, the proper growth of intelligence becomes entrapped by a closed, inertial life. Lest we forget, the madrasa-going student-body is also a part of our wider, vigilant student society; just as the school-college-university-going students are the future of the nation, so are the madrasa-going ones. But I do not think that anyone has ever given equal importance to this matter. Hitherto, the madrasas have remained just a trivial footnote in the reports processed by the Ministry of Education. Even the progressive political parties of the country hold the view that the madrasa-students are not concerned about the state of the country and its society. Many come to the conclusion—without any exploration and observation—that each madrasa is like a citadel of reactionism; that no socially conscious, patriotic, political or cultural personality can emerge from them. Needless to say, this is a very biased point of view. Many of the non-communal and progressive personalities of the Indian sub-continent came with a madrasa-background. Figures like Mawlana Abul Kalam Azad, Mawlana Muniruzzaman Islamabadi, Mawlana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani were all madrasa-educated. Whereas the Muslims who received western education from the Aligarh University in British India adopted a policy of appeasement towards their British colonial masters; the Alems of Deoband Madrasa did not think twice in taking a directly anti-British stance. Comrade Muzaffar Ahmed, known as the founding father of the Communist Party of India, also went to madrasa as a boy. So, the notion that the madrasa students are not socio-politically conscious is not true at all. It is not true, and cannot be true, that madrasa students are all reactionaries, that they do not have any affection and love for this country. This is nothing but prejudice towards them. In spite of many changes in our political landscape during the last thirty years, this deep rooted misconception still prevails. No progressive political party or student organization has come forward with genuine good will to engage in dialogue or to discuss with the madrasa students regarding their wants and needs, and what their thoughts are for this country. Nobody has tried to politically organize the madrasa students for introducing them to the ideals of a modern state and to contemporary social thought.

The main reason behind this being the political parties and their student wings are mostly controlled by the bourgeois, petty bourgeois and their family members. If investigated we would find that, usually, children from working and lower-class families go to madrasas. Those who cannot afford to go to school but have thirst for knowledge sometimes get admitted to madrasas. The parents who are not affluent enough to send their sons to schools, seeing no other alternative, send them to madrasas instead. The madrasas run on zakat, sadaqah and various kinds of charitable donation from pious Muslims, which cover the educational and other expenditures of these poor students. Apart from these, only a handful of parents send their offspring to madrasas for giving them a religion-based education.

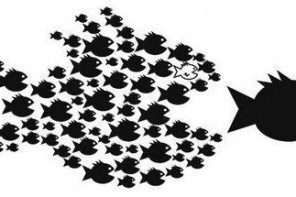

Rabindranath Tagore once famously wrote: “যারে তুমি নিচে ফেল সে তোমাকে বাঁধিবে যে নিচে / পশ্চাতে রেখেছ যারে সে তোমারে পশ্চাতে টানিছে”; which roughly translates: “Who you throw down will keep you tied there / Who you left behind would pull you backwards” No forward-looking political forces or their student-bodies have tried to take the madrasa students on board. The result is that they remain ever present as a dead weight in the path of progressive political and student movements of the county. Let us imagine that a social revolution happens here and the madrasa students do not oppose it. Nevertheless, that revolution would not bring about any positive social change as secular education is still not universal in our country. Religious traditions and customs still control many aspects of the social and cultural life of this country. The evil forces countervailing social revolution and progress breed discontent amongst the general people by branding revolutionary activities negatively. This happens in every country. But in our country, this problem will take a more acute form. Those who do religion-based politics use the bigotry of backward-looking people within the internal structure of our society to thwart any attempt towards achieving social progress. I do not think anyone has really thought of any strategy to confront this challenge. If political and social enlightenment came to the people of our villages, and if madrasa students having religious knowledge could be involved in organizational and campaigning activities then these endemic obstacles could be easy to overcome. Considering their class-identity, the madrasa students should have been potential revolutionaries. The reason they are not is that their thought-process in confined by the dungeons of the Middle Ages. None has ever knocked on their doors. If anyone had ever done so, at least a portion of them would have listened and responded. Those of you thinking afresh of social revolution, I hope, would contemplate the issue of madrasa students and would care to make them your comrades in future struggles.

The Daily Gonokantho

5th June, 1980

Ahmed Sofa (June 30, 1943 – July 28, 2001) was an eminent writer, intellectual and activist of Bangladesh. This article, originally written under the pseudonym Ananda, was complied in Ahmed Sofa Rachonaboli – Saptom Khando (Collected Works of Ahmed Sofa – Volume Seven), Nurul Anwar (ed.), Khan Brothers and Company, Dhaka: 2008, pp.310-314. Translated by Kazi Niaz Ahmed, who is a researcher at the Institute of Governance Studies (IGS), BRAC University. He is also the publisher or Foreign Affairs Insights and Reviews, a Dhaka-based bi-monthly magazine.