The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in Hamburg, Germany, delivered its judgment on the maritime boundary dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar (Case No. 16) on 14 March 2012. The judgment was rendered in accordance with Article 287 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 1982 (UNCLOS III), which states that member states may settle their disputes through any of the following means:

(a) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, established in accordance with Annex VI;

(b) the International Court of Justice;

(c) an arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VII;

(d) a special arbitral tribunal constituted in accordance with Annex VIII for one or more of the categories of disputes specified therein.

Bangladesh’s objection to India’s claims was filed with the United Nations Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), based in The Hague, Netherlands, under Article 287(c). The Indian claims overlapped with several of Bangladesh’s shallow and deep sea blocks, both within and beyond 200 nautical miles from its baselines. The PCA delivered its verdict on the maritime dispute between India and Bangladesh on 7 July 2014.

Law of the Sea

The present day Law of the Sea is the outcome of United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea of 1958, (UNCLOS I), UNCLOS II of 1960 & UNCLOS III of 1982. According to the UNCLOS III articles 3 & 15, every State has the right to establish the breadth of its Territorial Sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines in the line of low water tide along the seashore of a state. As per article 17, ships of all states, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea. Article 33 gives authority of a state on certain other matters to further 12 nautical miles called as Contiguous Zone. Article 55 allows an Exclusive Economic Zone, an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea, where the coastal State has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources. As per article 57, this exclusive economic zone shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines. The UNCLOS III of 1982 in its article 76 gives rights to the coastal states to own some more areas beyond the exclusive economic zone called the Continental Shelf.

Bangladesh Baselines

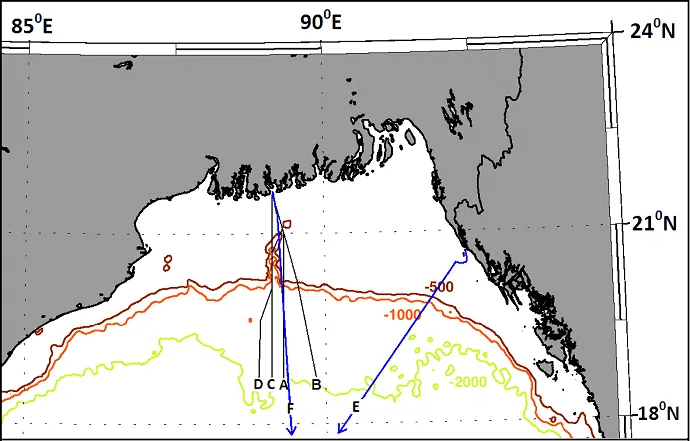

The Bangladesh coast from its boundary with India on Hariabhanga estuary to Kutubdia consists of many rising islands of mud. This is because about 1400 million metric tons of silt is being carried down annually by the Bangladeshi rivers from their upper catchments, of which the major amount is deposited into the sea. As there is no definite shoreline, Bangladesh drew its boundary limits with India during 1980s by following the silt flow line from Hariabhanga estuary to the Swatch of no Ground, and then another line along the 180 degree azimuth southward (Line A Figure 1). India wants to continue the silt flow line from Hariabhanga to southward which cuts across some exploration blocks of Bangladesh in the shallow and deep seas (Line B Figure 1). It may be mentioned that, maritime cartographer V.L. Forbes drew (1980) the maritime boundary of Bangladesh with India by one straight line from Hariabhanga estuary along 180 degree azimuth southward (Line C Figure 1).

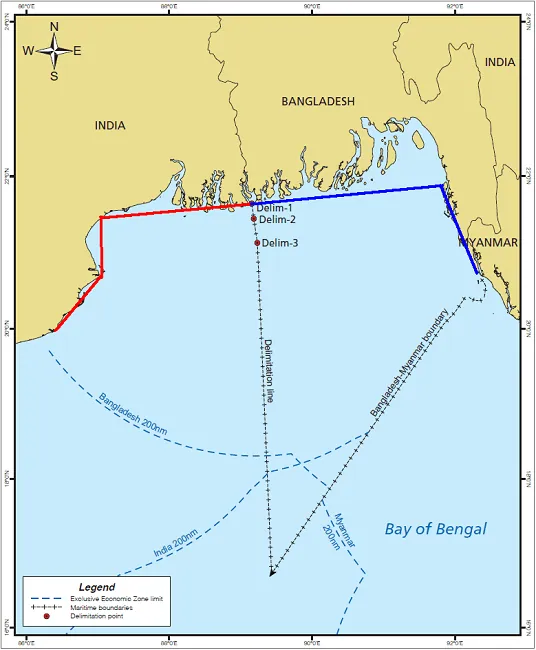

The Tribunal for Bangladesh & Myanmar drew (para 202, 204) baselines for both the countries. For Bangladesh, one line was from Mandarbaria Island (east of Hariabhanga estuary) to the Kutubdia Island and the other from Kutubdia to Naf River (land boundary terminus with Myanmar). The western boundary of the relevant area was drawn by a straight line from the Mandarbaria point towards south along 180 degree azimuth (Line C Figure 1). The relevant area was estimated 283,471 sq km on the sea, of which Bangladesh was awarded 111,631 sq km and Myanmar 171,832 sq km areas.

Maritime Boundary with Myanmar

Myanmar argued in ITLOS case 16 for an equidistant line following 232 degree azimuth from the Naf River outfall. Bangladesh argued that (para 213), on account of the specific configuration of its coast in the northern part of the Bay of Bengal, and of the double concavity characterizing it, the Tribunal should apply angle-bisector method in delimiting the maritime boundary between Bangladesh and Myanmar. Bangladesh claimed (para 217) its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the continental shelf (CS) by a delimitation line through the angle-bisector method, specifically through 215 degree azimuth line from 12 nm south of the St Martin’s Island. The tribunal limiting to12 nm Territorial Sea around St Martin’s Island (para 337) shifted the end of Bangladesh baseline at the outfall of Naf River. The tribunal however decided to deflect the equidistance line (para 340) for delimitation of the continental shelf, in view of the geographic circumstances of the case (para 329), to 215 degree azimuth to the southwest. The tribunal’s final judgment (paragraphs 500-505) states that the delimitation line along 215 degree azimuth shall continue until it reaches the area where the rights of third States may be affected (Line E Figure 1).

Bangladesh’s Maritime Boundary with India

Though the Tribunal in Hamburg awarded 111,631 sq km area of the Bay of Bengal to Bangladesh; some part of it was claimed by India on a 162 degree azimuth line from the mouth of Hariabhanga estuary. We argued on natural prolongation stated as per article 76 of UNCLOS III on the basis of bathymetric map of the Bengal depositional system. On that argument, India has no right anywhere to the east of Swatch of No Ground (Line D Figure 1), as sediment from Indian Territory does not reach there.

The verdict given by the PCA in The Hague on maritime disputes between India & Bangladesh, on 7 July 2014 is roughly shown by the line F in Figure 1. This verdict (article 509) has fixed three delimitation points from the land boundary terminus: (1) 21°38′40.2″N, 89°09′20.0″E (2) 21°26′43.6″N, 89°10′59.2″E & (3) 21°07′44.8″N, 89°13′56.5″E. From the third point it will be along a geodetic line that has an initial azimuth 177°30´00˝ until it meets the Bangladesh Myanmar delimitation line. According to the verdict, Bangladesh lost 6,135 sq km only, out of India’s claim on 25,602 sq km of area. The verdict arrived with four votes to one as Dr PS Rao concurring in part and dissenting in part.

Bangladesh Oil & Gas Blocks

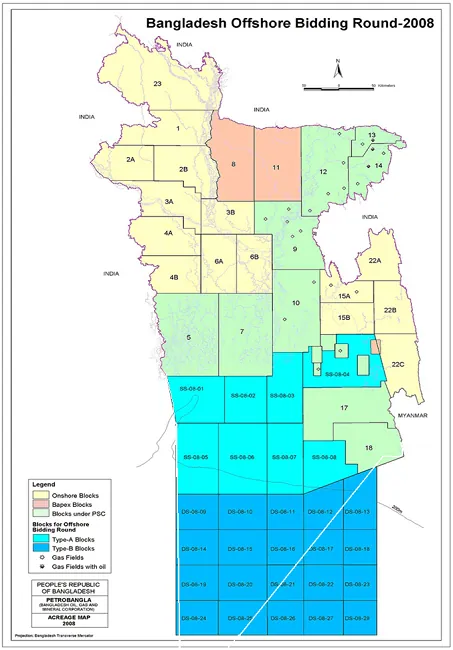

The verdict of ITLOS was not based on Natural Prolongation but on Equidistant Line from the baseline of Myanmar and Bangladesh. The tribunal decided to accept Angle Bisector Method argued by Bangladesh, and fixed the equidistant line following 215 degree azimuth beyond 12 nm west of St Martin’s Island. As a result Bangladesh could retain some oil & gas blocks in its deep sea but lost 200 nm EEZ beyond 12 nm south west of St Martin’s Island. Bangladesh also lost oil & gas blocks DS-08-18, DS-08-22, DS-08-23, DS-08-26, DS-08-27, DS-08-28 totally, and DS-08-13, DS-08-17, DS-08-21, DS-08-25 blocks partially. A part of the shallow sea block 18 was also lost to Myanmar. Bangladesh also lost a large part of the Continental Shelf beyond 200 nm EEZ.

ITLOS in its verdict estimated the Bangladesh relevant sea area to about 111,631 sq km. This area at 180 degree azimuth from the Hariabhanga estuary was never claimed by Bangladesh in the past. This amounted to about 6000 sq km extra areas west of our oil & gas blocks. The line given by the PCA verdict follows almost the western boundary lines of our blocks, but slicing out some portions from them. Thus the ITLOS & PCA verdicts can termed as were of equitable solutions.

With our maritime boundary settled with India we get 105,496 sq km area by tribunals. This area added with our 13,317 sq km internal sea becomes 118,813 sq km area. Though the tribunals gave equitable solutions, it has led Bangladesh to a sea lock position somewhere beyond 200 nm of its Continental Shelf. In that case we have to go to the high seas through neighbor’s waters. But however, use of the superjacent waters of one country by another country for some specific purposes, i.e., navigation and over-flight, laying of submarine cables and pipelines, etc., remain allowed as per articles 56, 58, 78 and 79, and in some other provisions of the UNCLOS II.

Engr. M. Inamul Haque is the Chairman of the Institute of Water & Environment, Bangladesh. He can be contacted at minamul@gmail.com